A famous poem by German poet Christian Morgenstern starts with the line that probably everybody has heard once: “Die Möwen sehen alle aus, als ob sie Emma hießen” which is in the translation by Karl F. Ross: “The seagulls by their looks suggest that Emma is their name”.

And in fact, if you think about it, isn’t the name Emma associated with a certain impression of a person, of a situation of a sentiment? The same is true for many other names and expressions. Because our mind is implicitly associating a linguistic meaning to words based on the sound denoting a concept that is expressed by the word going beyond the pure description.

Another good example is given in the New Yorker, that inspired this article, which quotes in the issue from May 2013: “Dawdle” and “meander” sound as unhurried as the walking speeds they describe, and “awkward” and “gawky” sound as ungainly as the bodies they represent.

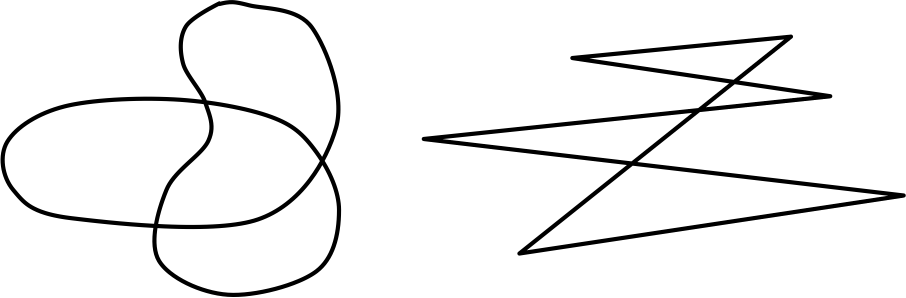

This observation led the German Gestalt-psychologist Wolfgang Köhler in 1929 to perform a psychological experiment to measure the non-arbitrary mapping between speech sounds and the visual shape of objects. In a famous experiment, which is now known as the Bouba/Kiki effect (see Wikipedia here) Köhler showed forms similar to those below and asked participants which shape was called “takete” and which was called “maluma”.

I am sure if you think about this for a moment you go with the vast majority of the respondents who associated the round and soft shape on the left with the word “malumba” while “takete” apparently seems to represent something jagged and sharp. In the following experiments using the words “kiki” and “bouba” 95% of participants selected the curvy shape as “bouba” and the jagged one as “kiki” in groups as diverse as American college undergraduates and Tamil speakers in India, implying that there seem to be deeper concepts to words we use. And if you are reading in a foreign language (like I do), didn’t it happen to you also that you didn’t know a word but somehow understood what it had to mean based on the sound?

You can see this effect also very clearly in the naming of products. Consider Clorox (producer of household bleach) and Chanel (high-end perfume). Switch the name and product and you get the idea. The words bear a subconscious meaning related to the sound. Sound elements in speech are called phonemes – which are related to morphemes in Grammar.

What has this to do with classification and document understanding?

Well, a good classifier will make use of these ideas to better train concepts and understand language. Meaning that it will not use a bag-of-words approach only, but break language down into smaller parts that allow to associate meanings with the phonemes. The Skilja Classifier follows this approach in extracting features from language.

Especially for short texts that are not very explicit and for sentiment analysis this method is far superior to using words. Take for example social media where words very often gradually change their meaning over time or new words are invented. But even if invented the new words follow the same sound pattern as existing words. We will use this approach for sentiment analysis based on pronunciation of quasi-words in Tweets. It will be interesting to see if the observed link between a meaning of a word and its sound can be statistically used to better understand sentiment.

Already today we see a significant difference in the quality of document classification if we compare pure word based classification with the richer statistics gained from morphemes. This is different from language to language with English being very sensitive while for example Mandarin does not show the effect at all as the symbols used for writing do not correspond to actual sounds.

We will follow up this interesting topic in number of future posts sharing ideas and results. For now let me just give you the final four lines of above poem by Morgenstern:

O human, you will never fly

the way the seagulls do;

but if your name is Emma, why,

be glad they look like you.